Let’s continue with the Pantah tribute texts. This motorcycle and its creators deserve more recognition than they seem to have. I own a “Motorcycles” book, which glances through the decades of motorcycles development. There are multiple Ducati’s or Cagiva’s described, but Pantah is so overlooked! I want to spend some time on appreciating what happened in the ’70s when Pantah was born and Fabio Taglioni proved his genius… once again.

The background

Beginning of the 1970s. Ducati was a well-established brand. Proven on the race tracks, having more history of technological advances than most of the brands on the market. They had the heritage, but they couldn’t compete with the sales numbers. While being performance focused and exotic brand – they were never centred on being cost-effective, and that was the problem. As “The Japanese invasion” was seriously threatening their market position. After flooding the market with cheap, reliable and very fast Honda’s at the beginning of the ’70s. Kawasaki, Yamaha and Suzuki followed. Ducati had to react, to the market demand and financial problems.

When the Italian government decided to help…

it made things worse for years to come. They proposed a new board of management to restructure the company. They knew they were secure in the L-Twin market with bigger displacements, but as the 1973 oil crisis hit, they needed to address the smaller engines segment and more affordable product range. Taglioni insisted on building a smaller L-Twin, but the management decided to be more cost-effective. They decided to create a parallel twin engine. Their logic was simple.

As a monolith of 2 cylinders working inline, without the need to duplicate the valves drive and header systems was potentially cheaper to build. And the Japanese, even despite the import taxes were able to sell well in Italy. The Ducati wanted to compete with them. Not only they decided to follow the technical concept of an inline engine – they even proposed a tax break for smaller displacement machines.

Taglioni didn’t want to participate in this project – and went back to develop his V-Twin further. So other Ducati designers took the job, starting with a clean sheet.

This theory didn’t work for Ducati

They managed to release a vibrating 360-degree crank parallel twin, but then jumped to a 180-degree. They went for chain-driven overhead camshaft 350cc and 500cc engines with spring valves. To eventually build a 500cc variant with desmodromic valves. The first versions were designated as GTL – Gran Tourismo Lusso.

As the 360-degree cranks required complicated balancing, that made the engines enormously big. After they switched to 180-degree cranks, the remaining space was utilised for wet sump reservoir. They also had complicated internal plumbing, that required frequent oil changes and keeping an eye on fluid levels. It seemed like it was too much engine – too little bike.

The engine size was addressed, as they hired well-known designers (like Giorgetto Giugiaro), that have delivered good-looking designs. But the public didn’t buy it. The showrooms were empty. Ducatisti were expecting more emotions.

The market was changing

Fiat 600 would do everything better than a motorcycle while being affordable and economical. For city riding – Vespa was there. The Ducati was supposed to be exotic and muscular. They didn’t see the excitement behind Ducati’s 750SS, Laverda’s 750 SFC, Moto Guzzi’s V7 Sport and Benelli’s 750 Sei.

This, connected with poor build quality was an issue. As the engines often didn’t survive more than 10-15k km. They couldn’t catch up with Japanese, who didn’t have any problem releasing better balanced, and way more reliable 2 or 4 cylinder engines. The management after two years of poor sales figures and reliability issues reached out to Taglioni. We are not yet at the Pantah, as the

Sport Desmo was halfway there.

Taglioni finally agreed to work on something else than an L-Twin, but immediately turned to desmodromic valve actuation and redesigned the heads. He used a pair of 30mm Dell’Orto carburettors. This allowed the engine to rev easily; exact horsepower figures are hard to find, but 53 horses at 9,000 rpm are the most common figures to be rumoured. For the design and bodywork – Leo Tartarini, who ran a successful firm, Italjet, was hired. He proposed Marzocchi suspension, Brembo brakes, alloy wheels. All this added to the Sport Desmo being too sporty and… made the price tag quite big.

The Pantah

Continuing to explore the cost-saving philosophy, but having in mind the previous market failures – Ducati decided to follow the route they know. Taglioni started to design a new model – The Pantah. But what made it great – it was inspired by existing models and components used before.

It was based partly on two existing Ducati race machines: 1973 Armaroli and a 500cc Grand Prix racer from 1970. Smartly borrowing from both – Taglioni created a motorcycle that can easily be labelled as a culmination of his life work. It combined almost all of his innovations in one small bike, that would be the conceptual foundation of the next 30 years for Ducati. Belt-driven cams, desmodromic valve system and trellis frame is the soul of what we know as a trademark of this Italian company.

While desmodromic valve actuation solved the valve float problem, was not the cheapest of the solutions. The belts that were driving the cams were on the economic side of the project.

Completing the prototype took less than six months

As they already had all the ingredients – it doesn’t surprise. Again it turned out that betting on an experienced designer paid off. It had the L-Twin layout with a 74 / 58 mm pistons and 9.5:1 compression ratio. It also used the 60 degree angled valves that Taglioni designed for the parallel twins a few years before.

The Pantah utilised a starter motor, a wet clutch and 5-speed gearbox. The iconic trellis frame held the engine via six mounting points. This concept was later easily extended from 500 ccs to 600 and 650 versions.

Initial prototypes from 1978 had 30 mm Dell’Orto carburettors, but production bikes used 36 mm ones. The power figures of the prototype were around 45 bhp at 9050 rpm. The design phase was finished early 1978. Due to bad management, production started with delays – September 1979.

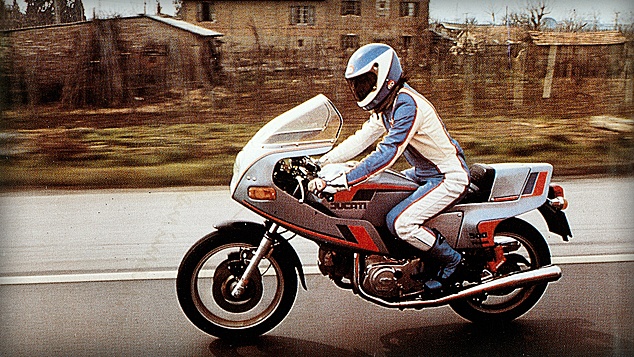

The first 163 Pantahs were red and silver.

The reception was average. In May 1981 Cycle Magazine complained about the bike running rich, having difficulties to start. The problems with jetting and long first gear made the Pantah performance figures suffer. It was only able to beat the Suzuki GS450 by half a second on a quarter mile, reaching 13,66 / 98,14 mph. There were also complains about the suspension.

But the gearbox while being not geared perfectly – was smoother and more precise than any Japanese counterpart at a time. The jetting problem was quickly fixed, the suspension upgraded and tuned. Making the Pantah a joy to ride.

Cagiva takes over

In 1983 Cagiva started sourcing its motorcycles with Ducati engines (350ccs to 1000ccs), entering the big displacements market. Two years later, 1985 – as the Ducati kept struggling with lousy management, Cagiva bought them. An amazingly bold move for a company that only started to produce motorcycles in 1978. As Ducati was a brand recognisable in the world – they decided to keep it alive – the factory in Bologne was kept operational. They started copying the Pantah model (among others) on the home market in their factory in Varese. That is why Cagiva “Alazzurra” (“Blue wing”) is often labelled as a Pantah twin.

One one hand – it’s quite sad how Ducati lost the market for a while and struggled with bad decisions. But on the other hand – Cagiva gave us more numbers of the Pantah to search for on the market. Making the bike more likely to survive!