Every interesting BMW model is described in source material with a quote: “Producer introduced this motorcycle to stop being labelled as boring”. It seems like an impossible task. For decades trying to break the stereotype, that just doesn’t let go. I don’t think they are boring though – it seems a lot like a hurtful stereotype. Probably born as these machines need some understanding. BMW is like Saab was for the cars – they always had a different opinion on how to build their products. You either loved it or…

This text is supposed to be about another of these “break the stereotype of a boring brand” examples. As (listing chronologically) they are the builders of a legendary military motorcycle, that didn’t have any competition. While being “lightly armoured transportation”, and serving on the wrong side of the front, it wasn’t dull. R75 Sahara to this day is an astonishing piece of engineering.

Many years later the same factories released a K-series. The first motorcycle with a flat longitudinal engine family. There was nothing like this back then and still – nobody copied it. The crown jewel of this segment was a BMW K1.

In the ’90s, another BMW machine was released, that tried to reinvent a segment dominated by H-D – a cruiser. A BMW R1200C… It’s only a fraction of motorcycles with a BMW logo, that made history. Maybe the reason for the “boring” statement is their lack of finesse design? That BMW is a geek brand, appreciated only by technically aspirated clientele? I can’t tell, as I try to understand both (design and engineering) sides of the fence.

Let’s focus on the topic.

The BMW R90S: Why was it so important?

The answer is… because of the Japanese “invasion”.

It’s 1971. Munich. An American, destined to transform the brand arrives at the office.

His name is Robert Lutz, a man that is a legend of the automotive industry, and he has a portfolio that includes brands like Ford, GM or Chrysler. A man who made quite an impact while working for the BMW for only three years. In 1971 he was appointed as an executive vice president of Global Sales and Marketing at BMW in Munich. While being responsible for the auto industry, he was overseeing a BMW Motorrad division, which at the time seemed like a burden rather than a prospering business.

The management had no idea how to sell their bikes. There was no defined strategy. Yes – they had the local market. The sales numbers while low, were stable, as their products were delivered to the police force and other public services in Germany. The regular sales were practically non-existent, it was especially bad in the US. The total of annual sales was about 10k bikes, which compared to Japanese brands was a disaster.

Lutz had his hands full with four-wheel products

…and yet he showed interest in motorcycles, getting to know what was going on. The engineers were doing their job without much effort – by merely upgrading the boxer engine every few years, salespeople couldn’t deliver results, the marketing didn’t work. There was no communication between company divisions. Top management was openly considering terminating this segment of the industry.

The rumour has it that Lutz needed to convince the board to let him work with the motorcycle division. Surprisingly they agreed – under one condition: he wasn’t supposed to neglect his main task in Munich – building sales strategy for cars and increasing sales in the USA.

So they got to work. While neglected, BMW Motorrad was still the best selling European motorcycle manufacturer; they couldn’t contend with cheap and revolutionary Japanese models. BMW needed a new product and a strategy.

They had the funds to design a new machine that could compete with the above, but Lutz played it safe – they stuck with what they had:

the legendary boxer engine

This was their legacy; their target client was very conservative and… they didn’t want to be accused of copying other brands (which was a kind of a plague back in the ’70s).

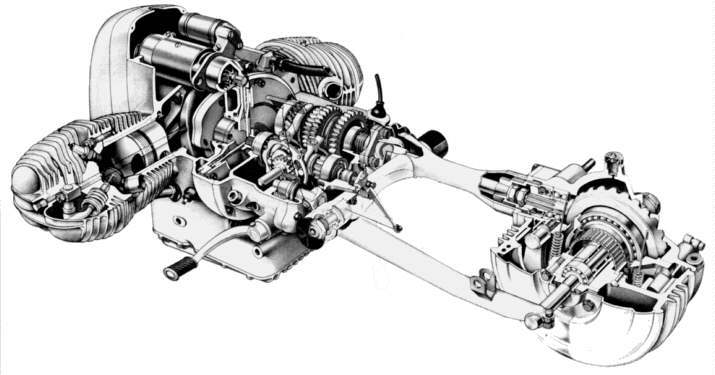

In 1969 BMW released their newest evolution of the flat-twin – R/5. It was the fifth generation of the engine with three versions prepared: R50/5, R60/5 and top: R75/5. They also had a good quality suspension available. The engines – on paper were not at all impressive, but they had their strong points. They were durable and had potential and engineering reserves to improve the power figures.

The head of the new project was Hans Albrecht Muth. His job interview recalled by his own words (with Hans-Günther von der Marwitz – head of development) seems like a perfect summary describing the state of things in the BMW Motorrad department.

“Since I did not particularly like the dash-five models, I asked him: ‘Who actually designs the motorcycles with you?’ Marwitz replied: ‘Nobody special! Do you like motorcycles, Mr. Muth? Then do it!’ And so I became the BMW motorcycle designer and did the job for a long time in parallel with the car interior.”

Fun fact: Muth in about ten years from this date was to be credited for the design of the legendary Suzuki Katana.

And with these circumstances – the R90S was born.

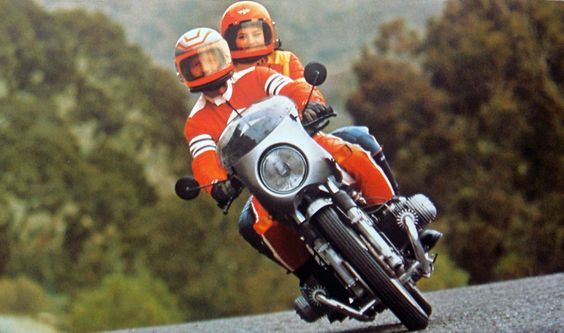

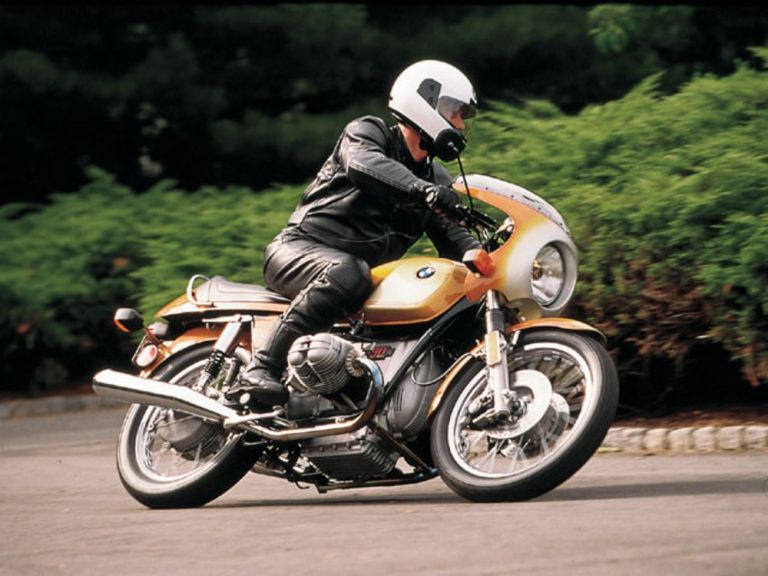

Muth and Lutz both quickly agreed that they needed to make a statement in the “sport” segment. The design process took 18 months. Technically based on the R75. Designing the looks, Hans was inspired by… aeroplanes and British performance bikes. In his vision, he needed to combine: German engineering, fighter plane vibe and British motorcycle tradition. Mutz was considering the machines with low handlebars (cafe racers?) but soon decided that this would be too radical. Instead, he chose to go with a fairing, which while allowing more traditional rider position, giving wind protection… made the looks more sporty and allowed to hide the instrument cluster.

Three designs were made

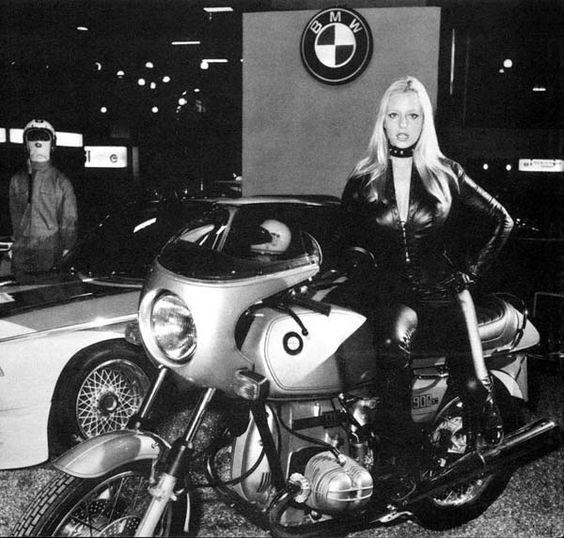

Lutz finally decided to choose one of them. But while the bodywork was approved – the new problem was identified: the paint job. Not a big deal You’d say… But back in the 70’s BMW offered three types of paintwork: black, dark blue and red (which was quite uncommon). R75 between 1969 and 1971 was available in only the first variant. While the competition was getting fancy with gradients and pinstriping – BMW had to improve. Mutz invented the Smoke Black/Silver composition, which was later inquired with women working in the factory. The most iconic paint scheme was born later… on the US racetracks – the legendary Daytona Orange and silver.

Back to tech stuff. The basis was the BMW R75, the goal – 200km/h and the handling that would deliver a confident ride. The engine upgrade was the first step. Displacement was increased to 898 ccs. New pistons and headers were used. What’s interesting – the smaller version crankshaft was left in place – a fact that proves the reserves of the construction. The fuel delivery went through 2 Dell’ Orto carbs. This setup generated 70 bhp, which through 5 gear transmission and a driveshaft were transported to the rear wheel. The suspension was tuned carefully, to make sure the handling will be capable of coping with the performance while providing a regular dose of comfort and confidence.

Stopping power was delivered by two brake discs

It was one of the first-ever production motorcycles to have this setup. When the project was ready, R90S was presented near the end of 1973 during the Paris Auto Show. According to Lutz – the motorcycle was a hit, gathering the majority of visitors attention. It was the first so well received BMW motorcycle. The design work was complete, and the market was now open. But…

BMW needed to set a price tag

And we all know that some things never change – it wasn’t cheap. Lutz admitted that the margin they made on each R90S was significantly more prominent than on few of their sedans. But they knew what they were doing – since the market reception was great, they already had reservations coming, for a motorcycle that nobody (besides the test drivers) had a chance to ride yet.

The concept was to market the R90S as an exclusive and expensive product for demanding clients, not the most popular one in the product range. The sales figures didn’t agree though. Despite the price tag, the demand was so big, that the factories couldn’t deliver on time. An important issue was the special paint job that was produced manually for each machine. There was also a problem with carbs availability. To meet the demands BMW decided to use stickers rather than manually paint the details and chose different carburettors, that resulted in lower HP values. These ideas – were quickly abandoned, and already sold models were recalled… at the expense of BMW.

The mentioned price tag of R90S was around 3500 USD. By comparison: Kawasaki Z1 cost was 1200 USD! The press was very unfavourable to the Germans for this, comparing both products side by side. The Saki was destroying the BMW on the engine side, but the handling was way worse. Things escalated when BMW decided to enter the motorcycle racing world with R90S… in the USA.

The history of R90S on the race tracks

…on the other side of the ocean started in 1971. Two years before R90S was introduced. Peter Adams, the owner of a company importing German products to the US, decided to race the BMW motorcycles. He founded his racing team and decided to use R75 as a base for a performance machine. The R&D team was assigned. The head of the project was Udo Geitl. The designated riders were: Steve McLaughlin and Reg Pridmore.

The most popular racing class back in ’70s was AMA Nationals, dominated by 2-strokes from Suzuki and Kawasaki. The Americans upgraded the R75 engine, changed the frame geometry and stiffness, improved the suspension… but they couldn’t compete with 2-strokes that had similar engine capacities. When in 1974 Yamaha TZ750 was introduced, it was clear that they didn’t stand a chance in this class.

But AMA back in the day was severely pressured by lobbyists (mainly from Japanese brands) to create a new racing class, where machines based on road motorcycles would be used. In 1976 – AMA Superbike was launched. It all started on Daytona 200.

R90S arrived to Peter Adams in 1974

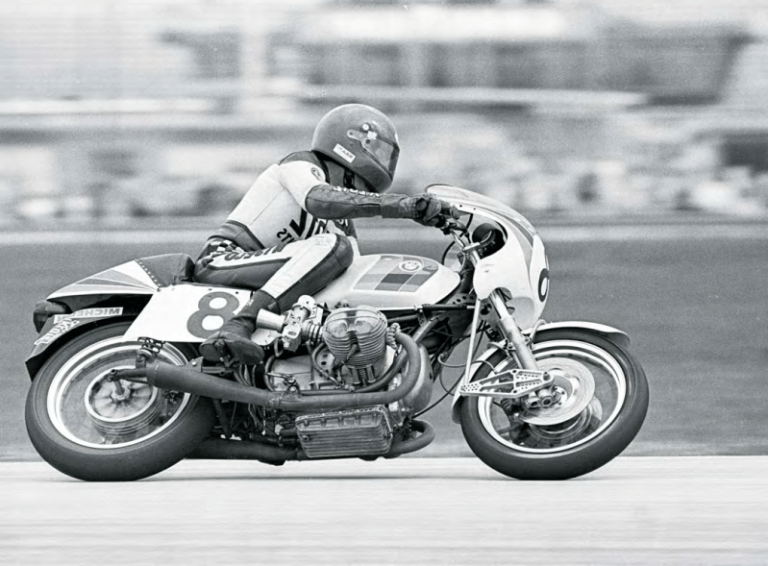

…who quickly recognised the improved engine had more potential than his previous choice. It took them two years to convert the road version to a racer. The budget was 250k USD. Seems like a cost of the front end of a currently used Superbike, but back in the day – it was a lot of money. The changes were extensive: Engine was upgraded, by increasing the displacement to 1000 cc, bigger Dell’ Orto carbs were introduced (40mm rather than 38mm stock), the compression ratio was increased to 12,6:1. It allowed the engine to produce 103 bhp. Quite an increase considering that it was around 70 bhp stock. And the weight of the machine was down to 175 kg.

The debut date was set – March 5th 1976, track: Daytona 200

The competition was strong. It’s worth mentioning that this is the time when Hideo Yoshimura had his crew on the racetrack. Udo Geitl decided to release two bikes, but Adams wanted to have a 3rd one, driven by a local rider. Udo agreed. On March 5th the team introduced three riders: Gary Fischer, Steve McLaughlin and Reg Pridmore.

It’s worth mentioning the motorcycles were different from each other. Reg Pridmore had a classic swing arm at the rear; two other guys had a redesigned, single shock version. It is rumoured that Pridmore declined to race with a modified swingarm, but it’s probably not true. The speculations are that it was a risk management move, just in case if two other bikes got disqualified.

During the qualification phase – BMW’s took top three positions. Fischer was first, Pridmore second, McLaughlin third. 4th was Cook Nelson on a Ducati. During the race – it seemed like Fischer was unstoppable. BMW’s were fast. Nelson managed to take the 2nd position for some time, but the other two guys were right behind him. Eventually overtaking the Ducati, and claiming top 3 spots for the majority of the race.

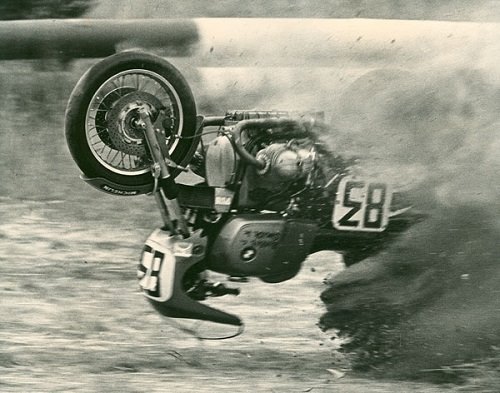

Unfortunately, Fischer had technical difficulties. His exhaust pipe failed, blocked the gear change lever, which resulted in losing it after a while – he had to retire from the race. Bikes number 83 (McLaughlin) and 163 (Pridmore) were left on the track. And they finished in this order.

BMW won the first race in AMA Superbike class

Nobody was able to anticipate that German manufacturer, stuck with the tech reaching the WW2, will be able to even hypothetically compete with the Japanese, especially knowing the state of things just three years earlier.

The second round gave the team 2nd and 3rd positions. Not bad. But the most critical event involving BMW team was about to happen during the third round – on Laguna Seca. The mechanics were working on the brakes between races. All machines were equipped with brake discs from Hurst-Airhead and two-piston callipers from Lockheed. During the race, Fischer retired due to oil pump failure. McLaughlin painfully discovered how the new brakes performed. Pridmore was first, McLaughlin right behind him. While in the previous two races – the teammates were easy on each other, not pushing it, testing… This time – the fight was on. During one of the turns, Pridmore made a mistake and lost some speed in the corner. McLaughlin caught him up too fast. Before he managed to react, it was too late… he pressed the brake lever, instantly lifting the rear wheel off the ground.

BMW number 83 went airborne

…the race was over for him. The photographer Mush Emmins was the lucky guy who caught the event with his camera.

It wasn’t over for number 83 though. Today – You can see this exact machine at the BMW Museum. The road it took to get there… from the rough sands of Laguna Seca roadside to Munich is a different story. But let’s get back to 1976.

BMW dominated the first season of AMA Superbike. A year later – they also performed exceptionally well. But the Japanese were busy. In 1978 Suzuki entered the AMA competition, working with Yoshimura they created an extremely fast machine based on GS1000. Kawasaki upgraded their flagship; Honda was about to introduce CB900F. Adams decided to resign from racing. He sold the bikes, to private owners, who kept racing them on smaller events but without any more spectacular successes.

BMW R90S also raced in Europe. Gus Khun was using it in Endurance racing – Le Mans and Bol d’Or. They managed to win on the Isle of Man twice. But it was the Superbike class that put the BMW back on the map.

Regarding the more down to earth history

R90S was produced between 1973 – 1976. So when they dominated the race tracks from 1976 – the model was not for sale anymore. Today – R90S is a classic and a quite important landmark for BMW. It wasn’t radical or revolutionary, but it got the job done. It convinced the decision-makers of the BMW Motorrad division to keep trying. That what You need to sell the motorcycles is a healthy dose of emotions. Lutz and Muth gave them the recipe for success. It was not necessarily the groundbreaking tech, but knowing what You want to achieve while remembering where You came from.

Shortly after the R90S production stopped, they introduced another “down to earth” legend – R80 G/S and soon after K100 was born. I can bet my lunch – that if it weren’t for R90S, we would never get to see the K100 and its successors.

Based on the original text by Jakub “Jabok” Ulaszek (youngtimerbike24.pl)